I love a fat book of short stories. A book big enough to block a dump truck. My major summer memories of boyhood are playing baseball until it was too dark to see the ball that was threatening to decapitate me and drifting lazily in all those stories, all those lives and times and places.

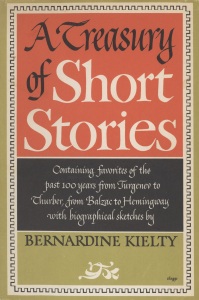

When I unearthed A Treasury of Short Stories at a used book store in Seattle, I was pumped. 849 pages in double columns. 77 stories. A hardcover with heft that had survived the journey from 1947 intact, including the dust jacket.

I don’t know much about the editor, Bernardine Kielty. She was born in 1890, maybe. She died in 1973, definitely. She wrote non-fiction and book reviews. The final page of the Treasury includes a brief biography with this sentence:

“As one of the first editors of Story magazine she participated in the discovery of many a fledgling writer since become famous, and as a fiction editor of the Ladies’ Home Journal she dealt with the stories of authors already arrived.”

Her publisher, Simon and Schuster, must’ve thought Bernardine was a goddess, because they not only paid her to assemble this juggernaut, they reprinted it 12 times, right through the 1950s. (I have the 12th printing.)

But when I finally plunged in, I almost climbed right back out.

Kielty made her first selections from the Jurassic era of the short story. The Treasury begins in Russia, and the Russians of the 1840s and 1850s had no idea what “brevity” meant. Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” is not a short story, it’s a marathon.

The French who follow the Russians in this lineup grasp the brevity concept, but like the Russians, their characters are caught in a rolling boil of ridiculous personalities, out-of-proportion reactions, and competing monologs instead of dialogs. Can’t anybody here play this game?

What saved me, and this book, was running into Robert Louis Stevenson’s first published story, “A Lodging for the Night,” on page 142. Stevenson wrote about the French poet François Villon (Anglicized as Francis) on a winter’s night in 1456 when it was so cold that starving wolves roamed the streets of medieval Paris. The story doesn’t end well, but Stevenson’s evocation of that frigid night is so persuasive that I almost put on a sweater.

I decided to stay. Two months later, I finished. Not every story was worthwhile, but the stories that were gave me plenty to think about:

Joseph Conrad’s “The Secret Sharer” might’ve seemed daring, even otherworldly, to its first readers in 1910, but today it can’t outrun a sexual subtext that Conrad never intended.

Or did he?

Ambrose Bierce’s “A Horseman in the Sky” has been anthologized many times, with good reason. It’s not sentimental, racist, inaccurate, or like any of the other drivel written about the Civil War. Its ending is similar to another much-anthologized story that’s not in the Treasury, “The Sniper” by Liam O’Flaherty, which is set during the Irish Civil War of the early 1920s.

Jack London can also work wonders with snow, as he shows in one of his most famous stories, “To Build a Fire.” The ending is inevitable and so seamlessly done that I wanted to applaud even though I’ve read this story more than once.

Frank O’Connor’s “The Storyteller” holds more sadness in a few thousand words about a little girl and her grandfather than in most novels. Roald Dahl’s “Beware of the Dog” makes an excellent start, putting you in the mind of a wounded British pilot trying to fly his plane home. Unfortunately, it soon turns into the kind of fake-identity spy story that was popular on 1960s TV.

Katharine Brush’s “Night Club” takes place in a ladies’ room. It was published in 1927 and might’ve been the inspiration for the all-female cast of the 1939 movie The Women. Brush is mostly forgotten today, though she was a best-selling author in the early 1930s and had movies made from two of her books.

(Yes, there are women in this book. Six women, 71 men. If Kielty had been a man, would this ratio have been even worse? Only one writer here is not a North American or European Caucasian: Richard Wright.)

These were my favorites:

Dorothy Canfield, like Brush, like most of us someday, is largely forgotten. Her story “Sex Education” gives us a single event retold and reinterpreted by one woman at three different ages. It’s an astonishing story told in everyday conversation while two women knit or visit. Canfield doesn’t break a sweat turning everything inside-out.

I don’t have to say anything about Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” beyond “Ernest Hemingway.”

The crowning story in the Treasury, for me, was Erskine Caldwell’s “Saturday Afternoon.” This is the single most chilling thing I’ve ever read, seen, or heard about the lynching of black men in the former Confederacy, and the black man here only appears in two paragraphs. It’s just another day. Caldwell wrote with great honesty about the poor, which is why schoolkids are given James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” to read and not “Saturday Afternoon.” (“Walter Mitty” is in the Treasury.)

I can’t imagine any publisher unleashing a book like this one on the reading public. 849 pages in double columns? Did people read more in the 1950s? My copy of the Treasury is unmarked and, before I got my hands on it, untouched. God knows what people in 50 years will think of what we publish today. I hope to be around then with a fat book of stories to read.